About this topic

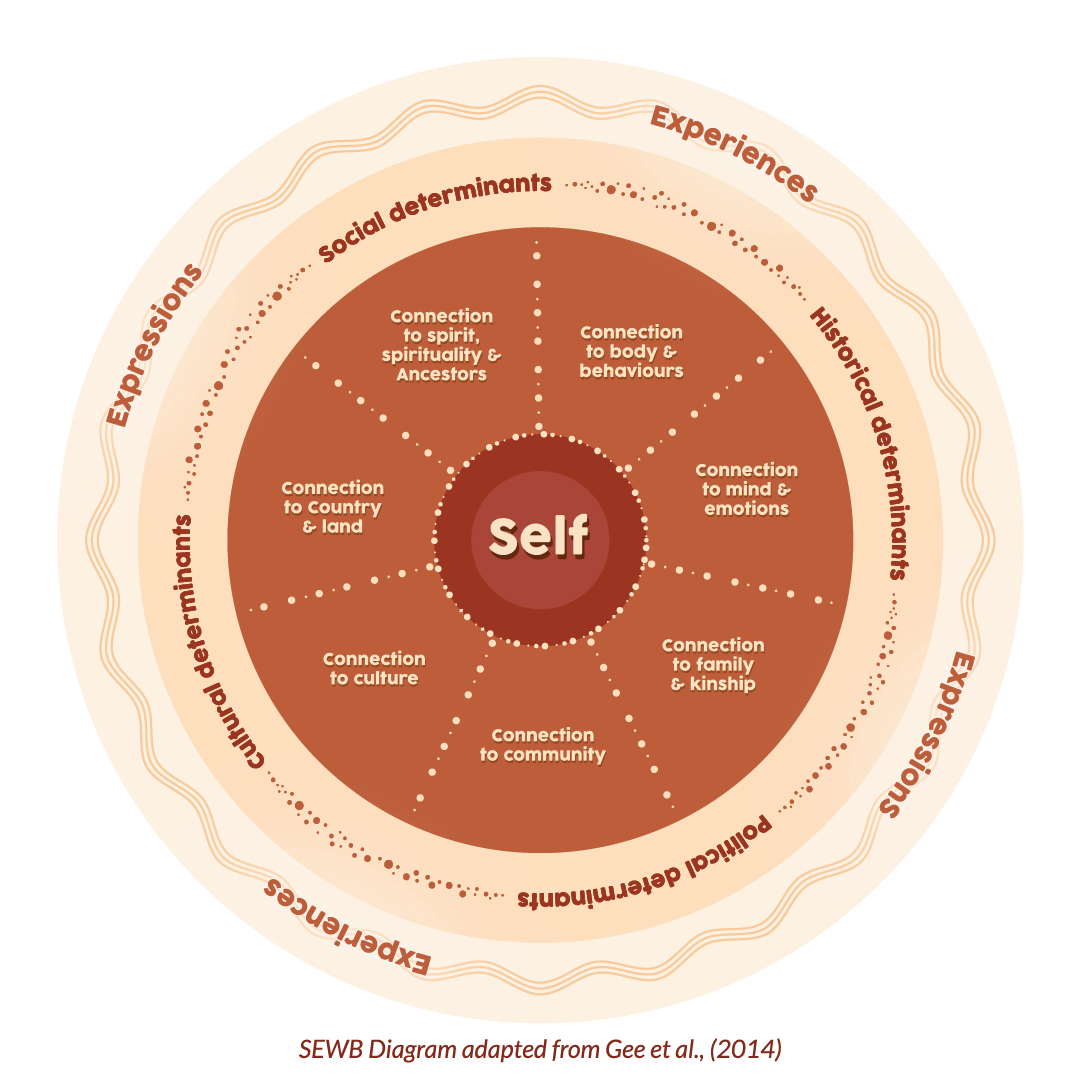

Social and emotional wellbeing is the foundation of physical and mental health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people. It takes a holistic view of health as it recognises that connection to land, sea, culture and spirituality all influence wellbeing. Social, historical and political factors can also affect wellbeing.

Social and emotional wellbeing is a collectivist approach to an individual’s self-concept: the self is inseparable from, and embedded within, family and community. Cultural groups and individuals have their own, unique experiences of social and emotional wellbeing (Gee et al. 2014).

Social and emotional wellbeing problems are distinct from mental health problems and mental illness, although they can interact and influence each other (PM&C 2017). Even with good social and emotional wellbeing, people can experience mental illness. People with mental health problems or mental illness can live and function at a high level with adequate support yet continue to have social and emotional wellbeing needs (AIHW & NIAA 2020).

In 2020, all Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations worked in partnership to develop the National Agreement on Closing the Gap- external site opens in new window (the National Agreement), built around 4 Priority Reforms. The National Agreement also identifies 19 targets across 17 socioeconomic outcome areas. Three of these targets directly relate to social and emotional wellbeing, monitored annually by the Productivity Commission.

National Agreement on Closing the Gap: social and emotional wellbeing-related targets

Outcome area 1: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people enjoy long and healthy lives

- Target: Close the Gap in life expectancy within a generation, by 2031 (from 11.4 years for males and 9.6 years for females in 2005–2007 to 0.0 years by 2030–2032 for both males and females).

- Status: Nationally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males born in 2020-2022 are expected to live to 71.9 years and females to 75.6 years, and non-Indigenous males and females to 80.6 years and 83.8 years respectively. This was a gap of 8.8 years for males and 8.1 years for females.

Outcome area 4: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children thrive in their early years

- Target: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children assessed as developmentally on track in all five domains of the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) to 55% (from 35.2% in 2018 to 55% by 2031).

- Status: Nationally in 2021, 34.3% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children commencing school were assessed as being developmentally on track in all five AEDC domains, which is lower than the target trajectory proportion of 39.8%.

Outcome area 14: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people enjoy high levels of social and emotional wellbeing

- Target: Significant and sustained reduction in suicide of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people towards zero (from an age-standardised rate of 25.1 per 100,000 people in 2018).

- Status: In 2022, the suicide age-standardised rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people was 29.9 per 100,000 people (for NSW, Queensland, WA, SA and the NT combined). To measure progress toward this target, a trajectory of a 75% reduction is presented on the Closing the Gap information repository. The 2022 rate is above the trajectory rate of 19.3 per 100,000 people.

First Nations perspective of health

The concept of health is complex, and there is no clear definition that is consistent across cultures. For researchers, practitioners and policy-makers to improve the health and wellbeing of First Nations people, it is important for a definition to be agreed. Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations were established in the late 1970s. Their efforts to define health from a First Nations perspective resulted in concepts that are based on holistic health, such as social and emotional wellbeing. In 2004, the National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2004–09 was established (Gee et al. 2014). It has 9 guiding principles that underpin social and emotional wellbeing:

- Health as holistic

- The right to self-determination

- The need for cultural understanding

- The impact of history in trauma and loss

- Recognition of human rights

- The impact of racism and stigma

- Recognition of the centrality of kinship

- Recognition of cultural diversity

- Recognition of Aboriginal strengths.

The Framework

The National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017–2023

The National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017–2023 (the Framework) proposes a model of social and emotional wellbeing with 7 overlapping domains:

- body

- mind and emotions

- family and kin

- community

- culture

- country

- spirituality and ancestors (PM&C 2017; Gee et al. 2014).

The Framework is intended to guide and inform mental health and wellbeing reforms affecting First Nations people in Australia. It describes the importance of social and emotional wellbeing for First Nations people and provides a model of it.

Background

The Framework was developed under the guidance of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Advisory Group. It was endorsed by the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council in February 2017.

Domains of social and emotional wellbeing

Social and emotional wellbeing views the self as inseparable from, and embedded within, family and community: the self is surrounded by 7 overlapping domains that are sources of wellbeing and connection. The domains support a strong and positive First Nations identity. The model also acknowledges that history, politics and society all affect the social and emotional wellbeing of First Nations people (Gee et al. 2014).

The 7 domains are:

Connection to body Physical health; feeling strong and healthy and able to physically participate as fully as possible in life.

Connection to mind and emotions Mental health; the ability to manage thoughts and feelings. Maintaining positive mental, cognitive, emotional and psychological wellbeing is fundamental to an individual’s overall health.

Connection to family and kinship These connections are central to the functioning of First Nations societies. Strong family and kinship systems can provide a sense of belonging, identity, security, and stability for First Nations people.

Connection to community Providing opportunities for individuals and families to connect with each other, support each other and work together.

Connection to culture Maintaining a secure sense of cultural identity by participating in practices associated with cultural rights and responsibilities.

Connection to Country Helping to ‘underpin identity and a sense of belonging’. Country refers to an area on which First Nations people have a traditional or spiritual association. Country is viewed as a living entity that provides. nourishment for the body, mind and spirit.

Connection to spirituality and ancestors Providing ‘a sense of purpose and meaning’. The mental health and emotional wellbeing of First Nations people can be influenced by their relationship with traditional beliefs and metaphysical worldviews.

Source: Transforming Indigenous Mental Health and Wellbeing

Key statistics

Estimated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population

The data presented in this section are sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians 2021. See the data tables in the Download data section for notes related to these data.

In 2021, First Nations people made up 3.8% of the population of Australia. This ranged from nearly one third (31%) of population of the Northern Territory to 1.2% of the population of Victoria (Table SEWB.1).

Most First Nations people lived in New South Wales (35% or 339,710 people) and Queensland (28% or 273,119 people) (Figure 1; Table SEWB.2). The proportion of First Nations males and females was about the same in each state and territory. The age distribution was also similar in all jurisdictions – the Northern Territory had the smallest proportion of people aged 0–24 years (46% compared with 50%–53%), while Tasmania had greatest proportion of people aged 65 years and over (7.3% compared with 4.1%–5.9%) (Table SEWB.3).

1. Final estimates of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, non-Indigenous and total populations of Australia at 30 June 2021 are based on results of the 2021 Census of Population and Housing. The Census counted 812,500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia (excluding Other Territories) on Census night. For more information about how the estimated resident population is calculated, see Explanatory notes in the Download data tables.

2. These estimates have been confidentialised. For more information see Explanatory notes in the Download data tables.

By remoteness areas, the proportion of First Nations people in the population ranged from 2.2% in Major cities of Australia to 47% in Very remote Australia (Table SEWB.4). Around two-fifths of all First Nations people lived in Major Cities of Australia (401,674 people). Fewer First Nations people lived in Remote areas than Very remote areas (58,727 and 92,146 people, respectively), with Remote areas having the smallest population of First Nations people of any remoteness area (Figure 2; Table SEWB.5).

The proportion of First Nations males and females was about the same in each remoteness area. The age distribution was also similar in all jurisdictions – Remote and Very remote areas had the smallest proportions of people aged 0–24 years (both 47% compared with 51%–54%), while Major cities and Very remote Australia had smallest proportions of people aged 65 years and over (4.8% and 4.9%, respectively, compared with 5.8%–6.3%) (Table SEWB.6).

Just over one third (34% or 116,051 people) of First Nations people in New South Wales lived in the NSW Central and North Coast Indigenous region (IREG), which was the IREG with the largest population of First Nations people in Australia. Port Lincoln – Ceduna in South Australia had the smallest population of First Nations people among all IREGs (3,380 people) (Table SEWB.7).

1. Final estimates of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, non-Indigenous and total populations of Australia at 30 June 2021 are based on results of the 2021 Census of Population and Housing. The Census counted 812,500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia (excluding Other Territories) on Census night. For more information about how the estimated resident population is calculated, see Explanatory notes in the Download data tables.

2. These estimates have been confidentialised. For more information see Explanatory notes in the Download data tables.

Social and emotional wellbeing scales

The data presented in this section are sourced from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS) 2018–19 and are for persons aged 18 and over. Estimates are calculated using a sample selected from a population rather than all members of that population. See the data tables in the Download data section for notes related to these data.

The 2018–19 NATSIHS included various scales that measured social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB). The Indigenous Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Clearinghouse (the Clearinghouse) has used 3 of these scales to identify relationships between wide range of factors such as disability, community acceptance and drug and alcohol use and SEWB.

The first measure used by the Clearinghouse was the Kessler-5 (K5), which is a modified version of the Kessler-10, used to measure psychological distress. The K5 has been designed for use with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (ABS 2019). High psychological distress is associated with mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety (AIHW & NIAA 2023a). High levels of psychological distress at a community level are associated with higher rates of suicide (AIHW 2022).

The second scale was the Pearlin Mastery Scale, which measured the level of mastery felt by First Nations people; that is, how much a person feels in control of life events and outcomes. High levels of mastery are important because they can reduce the effect of stress on a person’s physical and mental wellbeing (ABS 2019). Questions from this scale were only asked of people in non-remote areas.

The final scale used by the Clearinghouse was the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). This scale is used to measure a person’s perception of the level of social support they receive from family and friends (ABS 2019). Social support contributes to resilience and can reduce the effect of adverse life-events (Dudgeon et al. 2022). Like the Pearlin Mastery Scale, the MSPSS was only asked of people in non-remote areas.

Caution should be taken in ascribing the direction of relationships using the Clearinghouse analysis. While the analysis found associations between variables, it cannot determine the direction of the relationships nor the causal factors/variables.

Levels of social and emotional wellbeing

There was a slight difference between males and females in all 3 scales used by the Clearinghouse. The proportion of males reporting Low/Moderate psychological distress was greater than the proportion of females (73% or 163,100 out of 223,800 people, and 64% or 158,900 out of 247,700, respectively) (Figure 3; Table SEWB.8).

In non-remote areas, the proportion of males reporting High mastery was similar to females (67% and 64%, respectively). The proportions were similar for Perceived social support, with 62% of males and 58% of females reporting High support (Table SEWB.8).

1. Data reported for persons 18 years and over.

2. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to confidentialisation and rounding.

3. Persons excludes ‘Unable to determine’ responses.

4. Level of mastery and Perceived social support include people in non-remote areas only.

5. Data were collected from a survey sample and converted into estimates for the whole population. The overall coverage of the 2018–19 NATSIHS was approximately 33% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons in Australia. The survey results were weighted to the projected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population at 31 December 2018, which was 814,013.

6. For information about the measurement of level of mastery and psychological distress in the NATSIHS, see Explanatory notes in the Download data tables.

Around 7 in 10 (71%) of people in Major cities and remote areas reported Low/Moderate psychological distress. This compares with an average of around two thirds (65%) of people in regional areas. Level of mastery showed a similar pattern, with a greater proportion of people in Major cities reporting High mastery than in regional areas (Table SEWB.8).

Perceived social support had a slightly different pattern. People in Inner regional areas reported lower levels of Perceived social support (52%), but people in Outer regional areas reported similar levels of Perceived social support to people in Major cities (62% and 64%, respectively) (Table SEWB.8).

Psychological distress did not vary much between age groups, with around 68% of people aged 18–44 and 55 years and over, and 65% of people aged 44–54 reporting Low/Moderate psychological distress (Table SEWB.9).

Long-term health conditions and disability

Long-term health conditions are chronic conditions with a persistent impact upon health and with social and economic consequences that can impact on peoples’ quality of life. Long-term health conditions are the leading causes of illness, disability and death among First Nations people (AIHW & NIAA 2023b).

A disability may be an impairment of body structure or function, a limitation in activities and/or a restriction in a person’s participation in specific activities. A person’s functioning involves an interaction between health conditions, environmental and personal factors. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are at greater risk of disability due to increased exposure to factors such as low birthweight, chronic disease, preventable disease and illness (for example, otitis media and acute rheumatic fever), injury and substance use. Along with limited access to early treatment and rehabilitation services, these factors increase a person’s risk of acquiring disability. Such factors tend to be more prevalent in populations in which there is a higher unemployment rate, lower levels of income, poorer diet and living conditions, and poorer access to adequate health care (AIHW & NIAA 2023c).

Social and emotional wellbeing and long-term health conditions and disability

Among people with current and long-term health conditions, people with Eye/sight problems were most likely to report Low/Moderate psychological distress (64%), High mastery (61%) and second most likely to report High social support (55%, after people with Hypertension 58%), compared with people with other conditions (Table SEWB.10).

People with Mental Health conditions were least likely to report Low/Moderate psychological distress (37%) or High social support (48%). People with Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were least likely to report High Mastery (38%) (Table SEWB.10).

The proportion of people with a disability reporting a High mastery generally decreased as the degree of limitation increased, from 70% with No specific restriction (31,000 out of 44,300 persons) to 37% of those with a Severe/Profound core activity limitation (12,600 out of 22,500 persons) (Figure 4; Table SEWB.11). Level of mastery and Perceived social support followed a similar pattern (Table SEWB.11).

1. Data reported for persons 18 years and over.

2. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to confidentialisation and rounding.

3. Totals exclude ‘Unable to determine’ responses.

4. Level of mastery includes people in non-remote areas only.

5. Data were collected from a survey sample and converted into estimates for the whole population. The overall coverage of the 2018–19 NATSIHS was approximately 33% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons in Australia. The survey results were weighted to the projected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population at 31 December 2018, which was 814,013.

6. For information about the measurement of level of mastery in the NATSIHS, see Explanatory notes in the Download data tables.

Among people with one or more disabilities, the proportion of people reporting High/Very high psychological distress was smallest among people with a Sight, hearing or speech disability (45% or 47,700 out of 105,900 persons) and greatest among people with a Psychological disability (80% or 40,000 out of 50,000 persons) (Figure 5; Table SEWB.11).

Sight, hearing or speech disability also had the greatest proportion of people reporting High mastery (50%) and High social support (50%). People with Psychological disability had the smallest proportion of people reporting High mastery (21%) and people with Intellectual disability had the greatest proportion of people reporting Low perceived social support (18%) (Table SEWB.11).

1. Data reported for persons 18 years and over.

2. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to confidentialisation and rounding.

3. Total excludes ‘Unable to determine’ responses.

4. Data were collected from a survey sample and converted into estimates for the whole population. The overall coverage of the 2018–19 NATSIHS was approximately 33% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons in Australia. The survey results were weighted to the projected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population at 31 December 2018, which was 814,013.

5. For information about the measurement of psychological distress in the NATSIHS, see Explanatory notes in the Download data tables.

Mental health conditions, long-term health conditions and disability

Among people with current and long-term conditions, those with Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were most likely to also have a current mental health condition (73%), followed by Back problems (dorsopathies) (61%) and Asthma (57%) (Figure 6; Table SEWB.12).

1. Data reported for persons 18 years and over.

2. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to confidentialisation and rounding.

3. Long-term health conditions is a multiple response question.

4. Total includes current and long-term mental health conditions and excludes ‘Unable to determine’ responses.

5. Data were collected from a survey sample and converted into estimates for the whole population. The overall coverage of the 2018–19 NATSIHS was approximately 33% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons in Australia. The survey results were weighted to the projected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population at 31 December 2018, which was 814,013.

The proportion of people with a disability who also had a current mental health condition generally increased as degree of limitation increased, from almost one third (31%) of people with No limitation or specific restriction to two thirds (66%) of people with aSevere/Profound core activity limitation (Table SEWB.13).

Among people with disability other than Psychological disability, people with Head injury, stroke or brain damage were most likely to report having a current mental health condition (68%). People with Sight, hearing, speech disability were least likely to have a current mental health condition (43%) (Table SEWB.13).

Unfair treatment

Racism is a social determinant of health and influences health outcomes (DoH 2019). Racial discrimination deters and undermines community functioning and increases ill-health (AIHW & NIAA 2023d).

People who experienced unfair treatment due to being Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander were less likely to report High perceived social support (52%) than people who did not experience unfair treatment (62%). They were also more likely to report Low perceived social support (13% compared with 8.2%). However, there was only a slight difference in the Level of mastery between people who experienced unfair treatment (62%) and those who did not (66%) (Table SEWB.14).

People who avoided situations due to past unfair treatment were more likely to report High/Very high psychological distress (44%), Low mastery (51%) and Low social support (15%) than people who did not avoid situations (28%, 32% and 8.2%, respectively) (Table SEWB.15).

Data tables

| Table number and title | Source | Reference year |

|---|---|---|

| Table SEWB.1: Estimated resident population of states and territories, by Indigenous status, 2021 | ABS Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians | 2021 |

| Table SEWB.2: Distribution of population across states and territories, by Indigenous status, 2021 | ABS Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians | 2021 |

| Table SEWB.3: Estimated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, by state/territory, sex, age, 2021 | ABS Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians | 2021 |

| Table SEWB.4: Estimated resident population of remoteness areas, by Indigenous status, 2021 | ABS Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians | 2021 |

| Table SEWB.5: Distribution of population across remoteness areas, by Indigenous status, 2021 | ABS Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians | 2021 |

| Table SEWB.6: Estimated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, by remoteness, sex and age, 2021 | ABS Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians | 2021 |

| Table SEWB.7: Estimated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, by Indigenous Region, sex, 2021 | ABS Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians | 2021 |

| Table SEWB.8: Social and emotional wellbeing among First Nations people, by sex, remoteness, 2018–19 | AIHW analysis of ABS NATSIHS | 2018–19 |

| Table SEWB.9: Psychological distress among First Nations people, by age group, 2018–19 | AIHW analysis of ABS NATSIHS | 2018–19 |

| Table SEWB.10: Social and emotional wellbeing among First Nations people by long-term health conditions, 2018–19 | AIHW analysis of ABS NATSIHS | 2018–19 |

| Table SEWB.11: Social and emotional wellbeing among First Nations people, by disability status and type, 2018–19 | AIHW analysis of ABS NATSIHS | 2018–19 |

| Table SEWB.12: Presence of mental health conditions among First Nations people, by long-term health conditions, 2018–19 | AIHW analysis of ABS NATSIHS | 2018–19 |

| Table SEWB.13: Presence of mental health conditions among First Nations people, by disability status and type, 2018–19 | AIHW analysis of ABS NATSIHS | 2018–19 |

| Table SEWB.14: Social and emotional wellbeing among First Nations people, by experience of unfair treatment, 2018–19 | AIHW analysis of ABS NATSIHS | 2018–19 |

| Table SEWB.15: Social and emotional wellbeing among First Nations people, by whether avoided situations due to unfair treatment, 2018–19 | AIHW analysis of ABS NATSIHS | 2018–19 |